Dear Andy,

Wow, it’s been a while since we last spoke. I’m about to start my junior year—can you believe that? It still seems like yesterday that you and I met through South Boston Afterschool. On the T-ride to South Boston, we talked in Chinese (I had just started; you helped me with my tones). We talked about girls (we talked a lot about girls). And sometimes we talked about more serious things. About how we were so afraid to fail, about how we constantly felt pulled in all directions. About how hopeless we felt.

When you quit South Boston Afterschool, I just figured it was a sophomore slump. Maybe your economics tutorial was taking up too much of your time, or maybe you were working on a new start-up, trying to be the next Mark Zuckerberg. You were stressed out the last time I saw you. I wasn’t too worried, though. I thought what everyone else here thinks: Junior year will be better than sophomore year. Senior year might be a bit tougher because of job searching, but you’ll be set after that. You’ll be a Harvard grad the rest of your life.

But then you jumped off a tower in downtown Boston. I thought wrong.

Andy, I spent a long time trying to figure out how to write this letter. It’s been on my mind every single day now for months. I almost gave up, because the words just wouldn’t come to me. It was too painful to express.

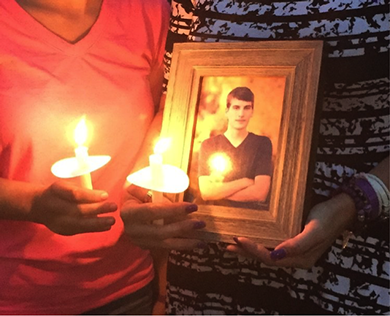

Then, in May, my best friend since we were babies ended his own life. He had just gotten into Georgia Tech. He had so much talent. He had such an incredible life ahead of him. His mom found his body. They couldn’t show it at the service.

His death inspired me to write this to you. Because it’s not just him, and it’s not just you. Writing this next part terrifies me, Andy. I’m scared because we live in a world where I can’t even write this letter without knowing in my heart that no matter what people will say, they will look at me differently. I want to make a big impact after I graduate, but I know that publicly discussing my complicated history with mental health—a conversation that should not be any more damning than talking about asthma or a heart condition—might prevent me from doing this. But that is exactly why I have to write this letter. It is time for us to reconcile with the reality of the world that we live in. It is time for me to say now what I should have told you before: You are not alone.

I should have told you about fifth grade, when I would stay up every single night thinking terrible thoughts. I had to make sure once, twice, three, four, five times that our doors and windows were locked, because I had to be sure. I had to know that no one would come in and slit my parents’ throats, and then beat my head in with a baseball bat.

I should have told you about sixth grade, when I touched flowers, and leaves, and people’s hair. My classmates did not understand, so they signed a petition asking me to stop. They gave it to the teacher, who presented it to me. Even today I remember the hurt and shame I felt when I saw the names of so many friends written on that piece of paper. They didn’t know that I could not help it; they did not know that it was outside of my control.

I should have told you about seventh grade, when germs consumed me. Bacteria crawled all over my body and inside my mouth. I would go to the bathroom repeatedly in the middle of class to frantically rinse my mouth and scrub my hands. When my best friend sneezed on me to see my reaction, and another spat in my juice and forced me to drink it, and another threw meat at me because she knew I was a vegetarian. I wondered if I had any friends at all. Maybe they were just pretending to like me because I was so funny to watch. I felt worthless; I felt hopeless; I felt powerless. I felt like I didn’t deserve to live.

But more important than any of that, Andy, I should have told you about how finally enough was enough. My mom got me help. She got me help, even when my teacher asked, “Why does he need therapy? He makes all A’s—he’ll be fine.” My mom replied, “I will be sure to write on his tombstone that he had all A’s after he kills himself because he hates his brain.” She knew what too few understand, that objective achievement means very little when life is nothing but shame and darkness.

Because of her intervention, I acquired tools to deal with my compulsions, to say “It Don’t Matter” until it really did not matter. Overcoming my compulsions was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but it was worth it. I’m here today Andy, writing this letter to you, because my mom got me help.

Andy, I am sorry that I never told you about my middle school self. And I am sorry that I never told you how therapy empowered me to reclaim the beauty in life.

But I hope this letter to you will help change things for others. I hope it will convince someone who is like me all those years ago to find the support that they need. I hope it will encourage someone like me now—too busy with their midterms, their finals, and their papers—to check in on a friend. I hope it will encourage us as a community to fight against the stigma surrounding mental health issues both in our college and in our nation. And most of all, I am sorry that we live in a society where we could not talk openly to each other.

I miss you more than you can know, Andy. By relating this story—of what I did wrong with you, and what my mom did right with me—I want us to make a difference in the world. Then I will know that I am doing your memory proud.

Will

Originally published in the Harvard Crimson, September 2, 2015

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In Reflection: Will’s thoughts on the process of writing and publishing this letter

At first, writing Dear Andy was pure catharsis. It was also extremely difficult. For years I had not been able to even talk about my history with mental health and the tragedies of my friends' suicides. To put my feelings into words for thousands of people to see would have been unthinkable to me. But after receiving support from my friends and my fraternity brothers, I found the voice to write my article. As a result of the attention that my article received, I am now working with a number of organizations on and off campus as well as Harvard administrators to improve mental health services. The feedback I have received since writing Dear Andy has inspired me to fight for mental health reform, both on campus and beyond. This has become my passion, and I am not going to give up until I have done everything in my power to change things.

William F. Morris IV is a member of the Harvard College Class of 2017 and is a joint concentrator in history and East Asian Studies.